Statistics is a hell of a drug — like a higher-than-healthy dose of Benadryl, it may cause hallucinations, delirium, sleep. It becomes a bit more palatable, though, when it sneaks its way into the rules of a game. It can give a bit of zest and unpredictability to board games, card games, and the narrative ups and downs of tabletop RPGs.

Players and gamemasters of Dungeons and Dragons knows that it can be tricky, but rewarding, to tune the odds of skill checks and random encounters — either to provide a satisfying outcome for the players you DM for, or to rig the odds minmaxing characters for successful outcomes. Things get real fun when you start mixing dice together. Advantage, disadvantage, or the thrill of rolling out eight or nine dice on a damage roll — it raises the unpredictability, but can also get tricky to calculate out the odds.

NOTE

If you’d like to mess around with the dice roll widget, you can find a copy and how-to at its dedicated page

Single Dice: No Convolution

It’s not too bad to roll a single dice. In a fair die, where each side has equal odds of coming up on top, the probabilities don’t get too complicated. Take, for example, a simple six-sided die (a d6):

| Roll | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chance | 1 in 6 | 1 in 6 | 1 in 6 | 1 in 6 | 1 in 6 | 1 in 6 |

| Percent | 16% | 16% | 16% | 16% | 16% | 16% |

Not too bad, right? It’s simple enough to do all of the math in your head. It can be subdivided easily — 3 or less and 4 or more each cover half the possible outcomes, so each has a 50/50 shot. If you wanted to, you could go as far as to graph out the odds, however boring and flat the graph would be:

What happens, though, when you need to roll two six-sided dice and add the results? Calculating the odds becomes a bit trickier, but it’s not anything that can’t be drawn out. By placing the outcomes on a grid and adding them together, a pattern emerges:

1st d6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

2nd d6 | + 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| + 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| + 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| + 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| + 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| + 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Outcome | Odds | ~Chance |

|---|---|---|

| 2, 12 | 1 in 36 | 3% |

| 3, 11 | 2 in 36 | 6% |

| 4, 10 | 3 in 36 | 8% |

| 5, 9 | 4 in 36 | 11% |

| 6, 8 | 5 in 36 | 14% |

| 7 | 6 in 36 | 17% |

We can see, here, that the sums stay the same through the diagonals of the grid. With seven sitting on the longest diagonal, it means that rolling two six-sided dice (2d6) has the highest odds at roughly 17%. Adding that with the odds of rolling a 6 or an 8, getting 7-ish comes in ~45% odds. That’s the reason why, in standard versions of Monopoly, the general advice is to buy the orange set of properties if you have the chance. With folks rolling their way out of jail, there’s a hotspot of probability 6-8 spaces away — smack dab in that neighborhood, with the Community Chest as an island of socialist reprieve.

I think that’s where statistics can get weird in people’s heads. The inclination is that adding two flat things together should give you another flat thing, but the way it spits out a curve feels off. That’s why taking the problem and putting it out on a grid can help — it helps work out why the numbers come out that way.

In probability and statistics, that idea of combining the two random outputs is called a convolution. There are certainly more intense definitions for the term, but at its root, it all comes back to that idea of taking a few possibilities and doing the same bit of math, again and again.

Working Out Advantage

In playing D&D, it’s not uncommon to roll a dice at advantage: you roll two dice, and have the good luck of getting to take the higher number and ignoring the lower one. It’s a nice boon — outweighed by the occasional disadvantage, where you roll the same two dice but keep only the lower one — and can feel like a massive improvement wherever you can get it.

I’ve heard, in the past, that getting to roll a twenty-sided die (d20) at advantage is roughly equal to getting +5 on a roll. When you have to think quickly about it, that’s not a bad rule-of-thumb to go with. However, it can’t be exactly like that. After all, no matter how many pure d20 you roll, you’ll never come out with a natural 25.

Looking at the actual odds, though, this ends up being another weird curve. Twenty sides is a bit much — but what does rolling a d6 at advantage (adv(d6)) look like?

Performing the convolution, we can just take the higher of the two dice rolls:

| A/B | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Outcome | Odds | Chance |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 in 36 | 3% |

| 2 | 3 in 36 | 8% |

| 3 | 5 in 36 | 14% |

| 4 | 7 in 36 | 19% |

| 5 | 9 in 36 | 25% |

| 6 | 11 in 36 | 31% |

This shows us the clear benefits to advantage. On the high end, we’ve doubled the odds of getting a six out of our single d6, and see that there’s a general upward curve to the odds of numbers on the higher end of the scale.

Bringing it back, then, to the d20 — what is the difference between d20 + 5 and adv(d20)?

It’s that slight curve towards the upper end at the spectrum that makes the difference. It makes sense that +5 became the shorthand, since that’s roughly the difference in the median roll (although +4 would be a bit more accurate, lining up the medians almost-perfectly). If you’re worried about rolling a 20 or above, +5 is very generous, giving you almost three times the probability. In the D&D sense, then, mechanics like proficiency or mastery may give you more bang for your buck (or XP) than, say, the chance to roll advantage more often.

Odds at Odds

These calculations can be incredibly helpful when randomness stacks on randomness, and especially when the choices you make in a game depend on the distributions of outcomes. In the last year, I’ve gotten into the game Magic: The Gathering to an extent that… I wouldn’t call it fiscally irresponsible, but I certainly won’t call myself a titan of finance, either.

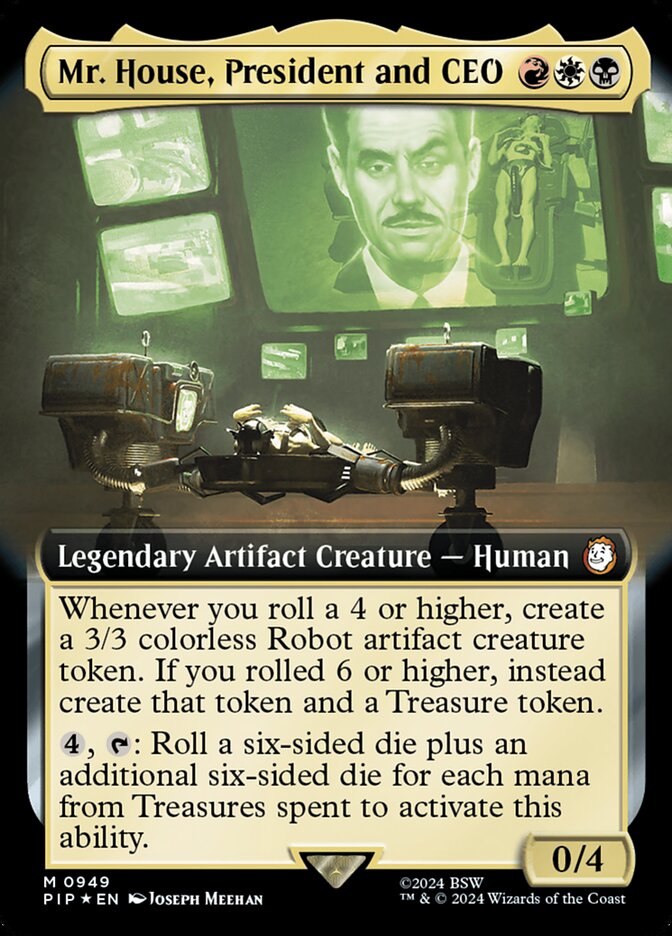

The deckbuilding aspect of the game is one of the greatest parts. Recently, to really shake things up, I’ve been building a wildly fun deck with Mr. House, President and CEO as the commander.

The card is phrased in a way that assumes you’re rolling six-sided die, but in a real “the house always wins” mentality, these odds can also apply to other dice — including our beloved d20.

There’s plenty of cards in Magic that allow you to roll dice to determine the outcome, but I can only fit 100 cards in a Commander deck. The hard part becomes: which to put in? Which to take out? If my goal is to roll higher than 6 as often as possible, is it better to keep a card that rolls 1d20, or a card that rolls 2d12? How many cards that grant advantage would it take to make a d6 as valuable as a d20?

NOTE

The

2d12is a bit more complicated than these widgets handle, since we have to take into account the chance of getting to roll higher than 6 with a single card, but it ends up being:

P(no rolls ≥ 6): 25%

P(1 roll ≥ 6): 50%

P(2 rolls ≥ 6): 25%

This complicates trying to use, say, expected values to measure it out. The E[

2d12≥ 6] is 0.50, but the variance is higher. That’s a hard one to gauge.

Some of the questions require different computation, but we can at least compare values. These types of visualizations can show the world of difference between the chance to roll a d6 and a d20. Aiming for a 6 or higher, the d20 is 4.5x as likely to net the result than a d6 (75% vs 16%).

Funnily enough, the target number does matter here — while the adv_8(d6) has roughly the same odds for rolling a 6, it actually has higher odds of rolling a 4 than the d20. If my goal was to maximize robots, it wouldn’t be as bad — it’s the goal of “roll as high as possible, as often as possible” that changes the game. Not that it matters — there’s only three Commander-legal cards that allow you to roll advantage, and only two fit with Mr. House, so the most I could ever get out of a d6 would be triple advantage — 42% (zeep zorp), not even a 50/50.

None of that, though, takes into account the additional effects of the card, or the occasionally insane amount of dice some cards let you roll at once. It also doesn’t take into account the psychological game. Even if the odds aren’t optimal, wouldn’t it still be satisfying to play Clown Car at 15d6?